Shackleton Over The Pond

John (Mo) Botwood

They were "Interesting Times"

None of them could be more interesting than the last month of the year. The chart in the "A" Flight Commander's office became the object of everyone's attention around mid-November in 1957. There was a green line starting at January and going directly to December with the squadron's allocated flying hours as the target. The red line that wobbled around the green, showed the progress of the squadron's actual flying hours, day by day. When it became obvious at the end of the year that the hours flown would not balance the Squadron's allocated hours, there was either nothing to do or there was a mad rush to accumulate as many hours as possible before Christmas. Last year the hours flown had outstripped the hours required and consequently the crews hung around the crewroom trying to find ways of passing the time. Winter in Northern Ireland does not lend itself to many outdoor activities.

November 1957 was typical of the latter case. Number 269 Squadron at Ballykelly had a red line that was short by 650 hours. So eight crews had to accumulate that amount in three to four weeks. To put it simply - make each sortie a fifteen hour Navex.

There were three Coastal Command Squadrons at Ballykelly, all equipped with Avro Shackletons. Numbers 269 and 240 flew the Mk I and 204 the later Mk II. Although different in appearance the two Marks had the same internal equipment. Each Squadron had nine aircraft and its personnel was split into two Flights. "A" Flight, of nine crews, each crew comprising two pilots, two navigators, one flight engineer and five signallers. "B" Flight consisted of all the ground crew specialists necessary for maintaining the front line operation of the Squadron.

Our main area of operations was the North Atlantic - sometimes called "The Pond". You could say that it is an intriguing part of the world. It holds so much history, both apparent and hidden. Rockall for example, a solitary landmark four hundred miles Northwest of Ireland, is a small rocky pinnacle sometimes sixty feet above sea level and at other times completely submerged. The Royal Navy claimed it for the United Kingdom in 1952 by landing a crewman from a Sikorsky Dragonfly to plant a flag. This was done on one of the Atlantic's quieter days, the flagstaff was still there in 1962. Within thirty miles of the lonely rock lie four U-boat aces and many of their victims. Both hunter and hunted lie together for ever.

Trans Atlantic air traffic was on the increase in 1957. The airline fleets consisted mainly of Super Constellations, Stratocruisers and DC 'Seven Seas'. The Comet and the Boeing 707 had commenced operations in September and October respectively and would soon change the scene. An average of 182 aircraft crossed in Mid Atlantic at 0200, usually 20,000ft above us. We could listen to their chatter on VHF, whilst on the HF band, the strange sounding chords of the four harmonic tones of the SELCAL could be heard. We did not have the required decoder, but we received the four harmonic tones loud and clear.

Many calls were to the Ocean Weather Stations. These ships were no stranger to the North Atlantic, having "served their time" protecting convoys and hunting U-Boats some 12 years earlier. They were converted corvettes and provided weather reporting to Europe and the British Isles. They could also provide direction finding, flare paths and Ground Controlled Approaches in an emergency. We would often exercise with them and conduct simulated ditchings to keep their Ground Controlled Approach operators proficient in their talk down procedures. We often operated with them in our Search and rescue role and looked forward each year to dropping Christmas mail and tree to our "local" Station Ocean Weather Station Juliett.

A typical Navex would be from 0600 to 2100 or 1800 to 0900. The 0600 flight started with an early morning call at 0300. Preflight meals would be taken in the Messes and of course would normally consist of bacon, eggs, sausages and beans. Then via either coach or van to the Operations building at 0430 where each specialist would self brief before gathering in the main operations room for general briefing. The pilots would come out of the Notice to Airmen and Mariners (NOTAM) office, the signallers would finish discussions with the Ground Radio Operators in the adjoining room and collect the codes of the day. The navigators would have been checking the wall board and daily charts to see if our paths would cross with any other operations. A typical briefing would have the Met Officer, followed by the Operations Officer giving an update on the intelligence situation on NATO and other forces in the Atlantic. Most days we would have the "Pond" to ourselves. If there was to be a depth charge drop, the promulgated area would be the subject of a NOTAM and it was not surprising to find the occasional trawler hanging about the site. Sorties could be easily planned on a triangular course, each leg lasting four hours with crew training being carried out on an opportunity basis. Cruising altitudes would vary between 500 and 1500ft depending on weather conditions. Fifteen hours and back home, this has to be the only Command where an aircraft leaves point A and after so long a time looking at nothing but sea, arrives at point A.

While the briefing was in progress, the groundcrew would have been working on the aircraft for hours. A fifteen hour flight required 3626 gallons of AVGAS, so with no fuel jettison system and a maximum take-off weight close to 81,000lbs this meant that once airborne, six to seven hours were required to burn off sufficient fuel to get down to landing weight. The armourers would be loading the weapons bay which had fifteen stations, each capable of carrying l,000lbs except the centre station which could carry a 4,000lb airborne droppable lifeboat. A normal training load would be 32 practice bombs (dropped in sticks of two, to mark the start and finish of a depth charge stick of six), six sonobuoys and four depth charges. The bombing practice was for pilots and navigators. Pilots dropped the depth charges from low level by eye and navigators dropped from 300ft using the bombsight. Practice runs could commence from any range and in the navigator's case were usually the result of a Radar homing from 8 miles. Sonobuoys were carried for investigation purposes and the depth charges as part of the annual allotment for proficiency training. You could see the results of a depth charge drop which is more than could be said for the annual drop of a Homing torpedo which would enter the water with a splash and spend the rest of the time out of view banging repeatedly against a "padded" submarine.

The conditions under which the groundcrew worked never failed to amaze us. High winds, snow, rain and freezing cold; it was always the same to them. You could return with an unserviceable engine and before you started unloading the aircraft the cowlings were off and they were working on the glowing red hot engine with frozen hands. Even overseas, they had to operate in unfriendly conditions, they would travel with us in the aircraft when we went on detachment and 269 was always proud of the close relationship that existed between the two groups.

Even in Ireland, it was cold in November and the passage of warm fronts would provide only relative and temporary relief. The flying rations were collected by the Duty NCO and taken to the aircraft. It could be quite a load as they had to provide meals for ten men over a period that covered three main meals. The only facilities on board were one hot plate with a hot cupboard above it and a hot water urn. Most crews took pride in making each main meal a three course meal. It was amazing what could be got away with under the dim aircraft lighting, creamed rice looked so much like scrambled eggs when served on toast to the navigator under his yellow lighting.

On arrival at the Squadron the crew would change into flying gear. On cold sorties most would wear a pair of flannel pyjamas under their uniform then a thick pullover, flying suit and cold weather flying jacket. A few still had the old issue sheepskin lined boots which were not only very warm but extremely comfortable. All safety equipment and the crew box, containing crockery, cooking utensils and cutlery, would then be transferred to the aircraft and preflight checks would be carried out. Pilots and the engineer would carry out the external aircraft and engine checks while the navigators checked the weapons bay against their load sheet (to make sure that what they hoped they were going to drop was what they actually dropped). Signallers would stow the gear in the aircraft as their checks could only be carried out with the engines running, the power from the trolley accumulator being too weak to drive both Radio and Radar. If time permitted, the crew would gather some distance off to have a smoke and savour the silence. The bulk of the aircraft would loom silhouetted against the lights of the station living quarters on the hill. It was a very reassuring sight. Our usual aircraft was VP287 a MkI. The Shackleton was the last of the Roy Chadwick designed piston "heavies". No one could ask for a better combination than an Avro airframe with Rolls-Royce engines. The overall dependability and surfeit of power did a lot for the peace of mind.

When it was time to go, the aircraft was entered by the door on the starboard side. Turning right to go forward, you turned your back on the Elasn toilet and passed the two beam lookout positions, the large stores of flares, sea markers and cameras. The next area was designated as the crew rest area but the two rest bunks were always full of parachute bags and more flares as this is where the illuminating flare guns were mounted. The four banks of six barrels fired one and three quarter million candle power flares - at one second intervals. The resulting string of pearls would light up anything within 3/4 of a mile. Just ahead was the Galley and the first of the obstacles, the flap activating housing with a cover a foot square. Then over one of the main spars past the radar station and over the big main spar three feet wide and high, past the navigators and sonics positions on the left side of the fuselage before passing between the engineer's position and the radio position, both of these being small forward facing areas behind the pilots. The two pilot's positions were next and, ducking into the nose, you arrived at the nose canopy with its bench seat for the bomb aimer and observer.

When all stations were manned, the four Rolls-Royce Griffon 57A V-12 engines, each producing 2,455hp would be started in the order of starboard inner, starboard outer, port inner, and port outer. This order ensured that any engine fires could be reached by the groundcrew without the problem of turning propellors. With their starting, the constant roar that would stay with us for fifteen hours commenced. Once all generators were on line and stabilised, the remaining equipment checks could be carried out. The radar scanner was in a chin blister on the nose which allowed performance checks against the hills of Eire across Lough Foyle. Its position would also allow 'reverse' GCAs onto the runways which showed up particularly well when wet - a distinct advantage at Ballykelly. Radio contact would be made by W/T on HF with Group in Scotland and the sonics operators would check the performance of the SARAH Homing equipment against a test set mounted in the control tower. While the navigators checked their GEE, LORAN and the recently fitted Decca navigator which we would be using on the Squadron's detachment to Christmas Island next June. The pilots ran up the engines and checked for mag drops. Because Ballykelly sits on an old sea floor and is surrounded by hills, everyone in a five mile radius was more than aware of the condition of the engines as the sound echoes around the countryside.

The preferred runway at Ballykelly was 26 and this was much more preferable than 20. On 20, the old seashore starts where the runway ends and the climb out gradient of the Shack then matches the profile of the hills. Taxying a Shackleton MkI in fresh winds was a test of skill and strength. There was no servo assist to any control surfaces and the tail wheel was castoring, so steering was accomplished by differential braking and variation of engine power.

After take-off clearance was obtained, we lined up, checked full and free movement of the controls and after selecting water methanol, applied power against the brakes. Griffons at full song sound sweet and very impressive and when the brakes were released the long take-off run would commence. Once airborne, most vibrations ceased and the engine noise subsided to a roar. The prototype Shackleton had soundproofing which was removed from the production models. No soundproofing could ever help the pilots who sat exactly in line with the eight contra-rotating propellors. The after take-off checks were followed by the engineer conducting a quick fumes check, after which all equipment could be switched on and normal routine commenced.

Radar was manned continuously by signallers, rotating through the position through the position every 45 minutes to ensure operator efficiency. Crossing coast checks entailed opening the bomb bay and running through weapon selection on the load distributor - if nothing fell off it was working correctly. Gunnery checks could not be carried out after the removal of the mid uppers earlier in the year. Qualified gunners would have to wait until the squadron re-equipped with the MkII with their nose mounted twin 20mm cannon. The mid uppers were a nice sunbathing position but would occasionally cause an early return to base if the gunblast removed the HF aerials causing a sbsequent loss of communication if the trailing aerial was ineffectual.

It would be dark as we tracked north of the Eire coast and set course over Inistrahull Lighthouse. The light of the lighthouse seen from above is a revelation as four or five beams are seen rotating like the spokes on a wheel with the angles between them determining the time intervals of the light flashes. Towards the rear of the aircraft the Galley would start operating on a rotating basis of relief every two hours. Coffee was served as soon as possible and after that, silence would descend on the intercom as crew members occupied themselves with their specialist tasks. The three petrol heaters would be 'fired up' (an expression that sometimes all too literally described the process) and pockets of warmth were established in various parts of the aircraft.

The radio operator maintained contact with Group using a Marconi TR1154/1155. It was a set that was designed in the 1940s for ease of use with minimum training with colour coded controls which linked frequencies and functions. Although low powered, it had a distinctive chirp that penetrated most static and quite long ranges could be achieved. One of the navigators would act as the en route navigator while the other would assume the role of tactical navigator if necessary.

They would be assisted in their navigation by the radio operator with HF/DF and CONSOL fixes. Drift was measured through a vertical drift sight or by the periscope mounted in the beam area below the aircraft, the latter being used mainly at night with flame floats. Navexs became very boring for those of the crew without jobs and many crews took this opportunity to change positions for training in becoming proficient in other areas.

Dawn would reveal the usual grey Atlantic with many whitecaps and large green patches where the sun shone through the clouds on to the sea. The normal cloud cover would dictate a cruising altitude around 800ft, visibility could be unlimited with the absence of haze or smog. Radar would pick up Rockall at 25 miles and a radar practice homing would take place with the operator calling the overhead position with "on top, now, now, now". There was always rivalry for proficiency and accuracy, errors of even 25 yards resulting in back chat among the crew. Rockall was the turning point for the southbound leg which crossed the major shipping lanes of the North West Approaches and normally resulted in many sightings to relieve the monotony.

Sightings could be infrequent and sometimes when they came there would be two or three. Last month for instance, we picked up two contacts slightly right of track at 18 and 26 miles. The ASV13's track marker eased the problems experienced with the old MkVII, which only had a heading marker. This resulted in the need for a complicated procedure of allowing the target to drift off port or starboard and measuring the angular difference half way to the target and then correcting by doubling the angle and turning the other way. The radar operator called out the range every five miles until the closest target was reported as 10 miles. The nose position reported sighting a large Passenger liner slightly starboard and on the horizon. The tactical navigator was running a plot and it was decided that this was the further of the two contacts. The closest of the two contacts disappeared at 7 miles and the run on that target was finished on directions from the tactical plot. Nothing was seen, with such a sea running, it would have to have been something large to have provided such a return at that range. We did drop a sonobuoy on the last known position and it was monitored as we headed for the liner. We took the opportunity to increase our stock of ship photographs with a few low passes on both sides. We noted that there was no one on deck - and couldn't blame them in this weather. The sonobuoy gave us a bearing on the liner but nothing else. The first contact went down as a disappearing radar contact and was reported as such.

Radar homings were carried out on most sightings. Most of them would be of freighters and small liners, larger liners like the two Queens and the United States being seen further south in the South West Approaches.

Lunch would be prepared during these activities and low level manoeuvring during photo runs providing interesting exercises in balancing and dexterity while eating. The meals could consist of four courses, chicken soup followed by steak and kidney pie with potatoes, peas and carrots; finishing with mandarin oranges and cream and coffee; all from tins! The habitability of the interior of the aircraft could have been better! The matt black finish and dim lighting became depressive after just a few hours - but after fifteen!!! Resting crew members found it hard to relax and soundproofing and other amenities would have improved rest and ultimately efficiency.

Six hours after take-off the engines required exercising of the propellor translation units. Each engine would be run through the range of boost and the propellors through the range of R.P.M.s. This provided a welcome variation to the normal synchronised roar. Prior to depth charge drops, we would climb to 3,000ft to check that the area was clear. At the promulgated time the position would be marked with a sea marker that would burn for two hours and the charges would be dropped singly. Everyone would want to see the results of the drop as it was an annual highlight. The drop would be made by the bomb aimer on a sea marker and a spare crew member would check the weapon's release by observing the bomb bay through a panel in the front bulkhead. Normally, the aircraft would be kept on a steady course to allow observer reports on attack results but in this case everyone wants to see the effects of the explosion so, after release, a quick turn allowed all a good view of the results. There was a brief time interval after the weapon entered the sea; then a circle of white water flattened the sea with a shock wave, a tall spout reached up 60ft before falling slowly and causing only a momentary halt to the progress of the Atlantic swells. All this happened in silence as far as we were concerned and, strangely, would have the appearance of slow motion. The remaining three weapons would be dropped and the sortie continued. It looked spectacular but in reality, the weapons had to be within 19ft of the target to be effective. Any attack on a submerging target had to be made within 30 seconds of it disappearing. Nine hours would have passed by this time and course would be set for home. Although the leg was four hours we would complete the detail with two hours on our local Radar buoy conducting bombing practice. The intercom would again fall silent as routine was resumed.

The heaters required constant attention and if there was one that would stay on all the time and be super efficient, it was always the one in the navigators' area, bringing complaints of it being too hot. The only crew members occupied were those involved in en route tasks and off duty members passed the time as well as they could. The galley supplied coffee and sandwiches and for variation added, the odd sheet of cardboard to the sandwich filling to see the reaction of those that were busy. Others off duty found their thoughts wandering as they passed the long hours. Books or other reading materials were rarely carried and as many sightings were made in transit, a lookout was always maintained.

The crew was a strange entity. New members served an apprenticeship before being accepted as capable by the rest. The simple reason being that each crew member had the ability to drag all the others along in his own destruction. Although coming from all walks of life they formed a close knit group, being inseparable and looking after each other, in particular, the new boys in the crew. Of course there were personality tensions and problems but they were always sorted out before becoming too big.

In parts of the aircraft the cold permeated flying clothing and members moved around the aircraft to seek warm areas and find company in talking to others. This never happened on fully operational sorties when all positions were manned and everybody had a specific task.

The sun would be setting as we headed Northeast toward the coast. It would be behind us as we headed for Ireland, we came out of the dawn this morning and we will arrive at the coast out of, and after, the sunset./ we would fly fifteen hours and not see land. The radar operators used these flights to practise different techniques in searching for contacts, switching "on" and "off" and searching by sectors in the hope of surprising any submarine that might be using its Electronic Counter Measures equipment to detect our presence. This area was a well known barren area for submarine operations - but one could always hope.

Radar would pick up the coastline at 45 miles confirming our tracking. The navigators would show no surprise at this (although one or two have missed Ireland in the past). The course would steadily close the coastline until the loom of Tory Island light was sighted on the horizon. We aimed to pass to the Northwest of Tory and set course for Inistrahull and Number Nine radar buoy.

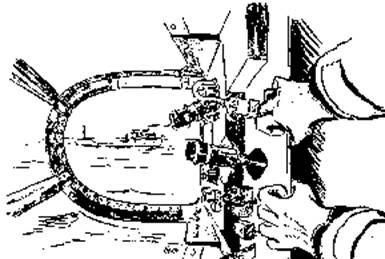

The radar buoy was a large moored buoy fitted with radar reflectors designed to match our radar frequencies. Before commencing operations, a safety check would be made of the area and communications established with Ballykelly on VHF. Night bombing is for navigator bomb aiming only and this detail would take more than an hour and a half.

Radar homings started at 12-10 miles, the operator gave headings until five miles and then directions left or right until on top. Distances from three miles were called as often as possible, the one mile call including the phrase 'Flares, flares' to start the illuminants. The bomb aimer took over when visual contact was made and the drop made using the bombsight. Assessment of the attack was made by the observer looking rearward through the bomb bay and was made in the form of percentages under and over the target for each bomb as they represented the start and finish of a stick of depth charges. A perfect straddle was with 50-50 no line error - the "line error" being distances left or right. The result was photographed with a rear facing camera using six photoflashes from an illuminants discharger in the roof in the beam position. After the run it was out to 10 miles again. The illuminants would be reloaded on the way and a turn would be made back towards the buoy for a repeat performance. Sixteen sticks of practice bombs could require 480 of the l.75 inch projectiles to he loaded and unloaded. The proposed flare activity would have been notified to the Coastguard and Lighthouse services earlier in the day. From the buoy it was only fifteen minutes transit to base and the lights of Derry could be seen reflected off the cloud base over Donegal - it all seemed so close - but the flight had to be fifteen hours long so more flying was needed. On most nights, those not flying were able to relax while sitting in the Messes, watching the pretty lights of the flare displays to the northwest.

After two hours of bombing, the transit to the circuit was made. Equipment and stores would be packed, washing up done and the aircraft generally tidied prior to landing. The crew brightened up as there would be no need for debriefing after a training exercise and it would be straight to the Messes on return. Early morning shaves would have long disappeared and everybody would be conscious of the fact that they had been wearing heavy clothing for almost 18 hours. There would sometimes be debate on whether the crew would be required to repeat the sortie the next afternoon as was the normal practice when flying hours were the main object of operations.

Crossing coast checks included a visual inspection of the bomb bay with the Aldis light to confirm that there were no loose weapons or hangups. Tracking in via Magilligan Point and sliding across the northwest face of Benenevagh, the field could be clearly seen on the banks of the Foyle. Benenevagh stands guard at the mouth of the Lough and is known locally as "Ben Twitch". Between Ballykelly and the mountain, the old airfield of Limavady is close to the hill. To warn crews of its closeness, a low powered radio transmitter was used. If the aircraft strayed close to the slopes. the transmitter activated the abandon aircraft klaxons. The circuit was such that it was on and off all the time - hence the "Twitch". Arrival was never a simple process, with the three squadrons and other units, there was always circuit traffic. There was also a further complication in that circuit lengths were sometimes affected by trains crossing the main runway before our arrival and they had priority!

After landing, a quick magneto check would be carried out before taxying to dispersal and parking under groundcrew directions. Numbers 1,2 and 4 engines would be cut, number 3 being used to provide services power to open bomb doors and lower flaps to rest the hydraulic system. When number 3 was cut an incredible silence would descend on the aircraft although you could still 'feel' the noise. The opening of the rear door brought a gust of fresh air which accentuated the 'Shackleton smell'; that strange mixture of oxygen, leather, sweat, Tepol, hydraulic fluid, paint and electrics - and the elsan.

Outside, the fresh Westerly felt marvellous and everyone would soon be changed and into cars for the quick run to the Mess. Driving off, one would experience the most notable and major effect of a fifteen hour sortie in a Shackleton; even the oldest Morris Ten would sound just as good as any Rolls-Royce.