BALLYKELLY - THE SHACKLETON ERA 1952-1971

DAVID HILL

PART 1 - A STATION REBORN

If you take the main road north out of Londonderry and travel up the east bank of the River Foyle, you will pass the sites of three wartime airfields. First is Maydown, now a large industrial complex, while the second, Eglinton, is now the location of the City of Derry airport. The third airfield is Ballykelly, situated on the shores of Lough Foyle, fifteen miles from Londonderry and two miles from the small town of Limavady.

U-Boat Success

The low-lying, farmland site was approved for the construction of an airfield in mid-1940, and an RAF opening party arrived to take over the partially completed aerodrome in June 1941. No operational units were based at first, but during 1942, No.120 Sqn. with Liberators and 220 Sqn. with Fortresses arrived to carry out anti-submarine patrols and convoy escorts over the Atlantic Ocean, with some success. In 1943 these units moved out and the base was taken in hand for upgrading to handle the later, heavier marks of Liberator, which were then planned. This entailed lengthening the main runway and providing additional hangar space, as Ballykelly was also to become a Liberator servicing and modification facility. It was at this time that the runway was extended across the main Londonderry-Belfast railway line. From late 1943 to the end of the war, Nos.59, 86 and 120 Squadrons at various times flew Liberators from Ballykelly in the long and tedious fight against the U-boats, ranging from the Bay of Biscay to Arctic waters off North Norway by day and also at night, using Leigh Light equipped aircraft. By the end of the war, Ballykelly-based squadrons had been responsible for sinking no fewer than twelve U-boats, sharing with other aircraft and surface ships in the destruction of several others, and damaging many more.

Care And Maintenance

The task completed, Ballykelly went to Care and Maintenance status late in 1945. However, as the Cold War era was starting, the need to counter the Soviet submarine threat was the next challenge. On the formation of NATO, the United Kingdom assumed a major anti-submarine role across the eastern Atlantic and North Sea areas. During the latter stages of the war an anti-submarine tactics school had been established at the Londonderry Naval Base, and afterwards this idea was further developed into what became known as the Joint Anti-Submarine School (JASS). Commanded jointly by RN and RAF personnel, JASS was officially opened on 30 January 1947. The unit had its own air elements, Royal Navy Barracudas of No.744 Sqn., based at Eglinton and the RAF's JASS Flight, based at a now re-opened Ballykelly, initially equipped with two Lancasters, one Warwick and one Anson. The task at JASS was to run courses to train the crews of ships and aircraft in the broader aspects of anti-submarine warfare, with emphasis on the development and application of combined tactics. There is more about JASS later.

Another unit, which was based around this time, was the Air Sea Warfare Development Unit (ASWDU), arriving from Thorney Island on 27 May 1948. The Unit's task was the development and testing of new maritime equipment, and in the course of this work had used a variety of aircraft types, but by the time it settled in at Ballykelly was mainly equipped with Lancasters. On 10 May 1951 ASWDU moved on to St.Mawgan, but was to return to Ballykelly in later years.

Post-War Expansion

Further development plans were in hand which would affect the future of Ballykelly. Immediately after the return to the USA of the Lend Lease Liberators, suitably modified Lancasters fulfilled the RAF land-based maritime patrol requirement. With the expansion of the RAF's maritime strength, a new aircraft was being specifically developed for the task. This aircraft was, of course, the Shackleton developed by Avro from the Lancaster and Lincoln but a very different aircraft indeed. A number of bases in the UK were chosen to house the future Shackleton squadrons and Ballykelly, situated at the western extremity of the British Isles, was one of them. The plan was that the Shackleton should be used on the long ocean patrols into the Atlantic, with Gibraltar, St.Eval and Aldergrove earmarked as bases as well as Ballykelly. The Neptune, bought from the USA as interim equipment until sufficient Shackletons became available, was to cover the North Sea area from Kinloss and Topcliffe. In early 1951 the airfield closed to non-essential flying for further upgrading to change it from a typical wartime aerodrome with fairly basic facilities widely dispersed, into a station equipped to support three maritime patrol squadrons.

Grin and Bear It

There was no middle ground with Ballykelly; you either loved it or hated it. The advantages were many; long sandy beaches close by, friendly but somehow different local population and, in the early days at least, access to unrationed fresh food from across the border in Donegal. You could even cycle there- up to Lisahally, boat across to Culmore, walk to Muff and there you were! A popular destination was Buncrana, where a certain restaurant (could it have been the Lake of Shadows?) reputedly sold steaks so enormous that they literally extended over the edge of the plate!

The main disadvantage was a feeling of isolation in an unfamiliar environment, you couldn't jump on a train and get to your destination relatively quickly- there was always a boat journey across the Irish Sea to be negotiated which complicated things, so much so that many personnel viewed Ballykelly as an overseas posting. As far as aircrew were concerned, they arrived as part of a crew that had generally been together since the start of training. Many of the members were very young, maybe eighteen or nineteen and they tended to stick together and socialise together. Apart from the messes on the camp Limavady offered a couple of cinemas, one of which allowed you to bring your bicycle into the auditorium with you and lock it to an iron bar provided for the purpose! Watering holes included the Alexander Arms Hotel and Henry's Bar, with regular dances being held in the Agricultural Hall.

A feature of the station, whether unique or not isn't known, was the rearing of pigs in some disused huts - whether they flew or not isn't known either!

At the outset, living conditions for the based personnel were little changed from the war years; cold, damp, leaky accommodation, in some cases remote from the airfield proper, such as on No.4 Site or Trenchard Site as it was grandly known. Bicycles and oilskins were the order of the day. The airfield was prone to flooding after prolonged heavy rain, the problems caused by this occurrence perhaps giving rise to the Station motto - nos difficultates non terrent - our hardships do not deter us! The non-operational facilities were fortunately located on a slight rise just above the airfield itself, which was reached by a long straight road, which brought you down on to the airfield near the threshold at the 03 end of the secondary runway. Although rough and ready you just had to make the best of it and most people usually did and became very fond of the area, although for the unmarried personnel living on base, there was comparatively little contact with the local people. Aircraft from other Shackleton squadrons were constantly visiting to attend JASS, which meant that there were usually some old friends arriving from OCU days and an excuse for a party!

An operational hazard was the presence of high ground surrounding the base on three sides, Benevenagh or Ben Twitch, as it was known at Ballykelly, some five miles to the northeast being a particular danger. It was called Ben Twitch as a result of wartime operations at the nearby Limavady aerodrome requiring a warning to aircraft operating in the vicinity of Benevenagh. This was achieved by mounting a low powered non-directional radio beacon on the hillside which activated the alarm klaxon in the aircraft whenever they got too close. The unexpected alarm caused the twitches which gave it its name.

By early 1952 the base was considered ready to become an operational station in No.18 Group, Coastal Command, and the association between Ballykelly and the Shackleton, which was to endure for nineteen years, was about to begin.

PART 2 - THE EARLY YEARS (1952-1955)

Above - WB849 of JASS Flight, 1952. Photo via David Hill.

At this time JASS Flight were the only unit at Ballykelly which positioned the individual aircraft letter as shown on the nose. The unit was also different in that their aircraft carried a black band round the outer wings and round the mid fuselage. At the end of 1954 the three Mk 1's were replaced by Mk 2's and the unit disbanded in March 1957.

A feature of the build-up of the Shackleton force was the formation of new squadrons out of existing units. Trained crews from these squadrons joined new crews graduating from No.236 OCU at Kinloss to form the new squadron.

Squadrons Arrive

At North Front, Gibraltar No.269 Squadron formed out of No.224 on 1 January 1952, being granted all the oldest aircraft 224 possessed, including one example which was undergoing repairs after hitting the sea wall on landing at Gibraltar! On 14 March the new squadron moved to Ballykelly taking up accommodation on the south side of the airfield, before moving into permanent premises at the northeast corner of the airfield on the far side of the main runway. Shortly afterwards No.240, formed out of 120 at Aldergrove on 1 May, moving the sixty or so miles from Aldergrove to Ballykelly on 5 June, immediately after participating in the Queen's Birthday flypast over Buckingham Palace. Later in the year the squadrons lined their aircraft up on the main runway with the crews paraded in front of them as the Queen passed by on a train on her way to Londonderry. Also around this time JASS Flight replaced its Lancasters with Shackletons, the first one arriving on 18 March with all three delivered before the end of the month.

Different Marks

All Shackletons delivered initially to Ballykelly were Mark 1's, with the ASV 13 radar scanner situated under the nose and a single non-retractable tailwheel. The Mark 2 was following closely behind and featured a more streamlined nose containing two 20mm cannon, with the scanner being moved amidships behind the weapons bay, which gave 360-degree search capability. A retractable twin tailwheel was introduced, with bays for vertical and oblique camera installations positioned just forward of a glazed observation position in the tailcone. Otherwise there was little difference between the two types. The brakes were still air operated but in the Mark 2 they were operated by toe pedals and lockable rudders on the ground to give the pilot better taxiing control. In the Mark 1 the brakes were selected by a hand-squeeze control that opened the air valve, one of the problems with this system was that in a crosswind without rudder locking the Mark 1 was almost impossible to taxi safely and there was numerous accidents.

At the outset the Mark 2 was not considered to be operationally different from the Mark 1, and as the later version became available, it was issued to the squadrons including 240 and 269, to be operated in parallel. Both types had a crew of ten, two pilots, two navigators, flight engineer and five signallers, whose job was to operate the radar and sonics, also manning the guns if required. Crews normally stayed together for long periods which helped to promote efficiency and a special sense of comradeship; indeed it has been said that a Shackleton crew was a party waiting to happen! In a large crew which worked closely together and depended upon each other to obtain optimum operational results, no single member could afford to do a sub-standard job, everyone else would notice. Combine this with inter-crew rivalry on a squadron and competition between squadrons, and it's not difficult to appreciate how highly Shackletons and their crews were regarded among their NATO allies.

Main Role

The Shackleton's main task was maritime reconnaissance and anti-submarine warfare. Search equipment comprised the ASV 13 radar, which could pick up a decent target up to a range of 40 miles in favourable sea conditions from an altitude of 1000ft. Poor sea conditions could, however, severely curtail the effectiveness of the radar return. On confirmation of a contact, a pattern of sonobuoys would be laid over the location and the position of the underwater contact deduced from the sounds picked up by the sonobuoys. At this stage sonobuoys were of the passive variety i.e. they only received sound from other sources, and did not transmit any sound signals of their own which could be bounced back off an underwater object. An attack would then be made using depth charges or, later and much less often, acoustic torpedoes. Shackletons also carried a large variety of pyrotechnics such as flares and marine markers, as well as rescue equipment for the SAR role. Visual search was also important, especially on search and rescue sorties.

Typical Operations

A typical operational sortie, if there was such a thing, could be a fifteen hour navigational exercise (Navex) over a triangular course over the North Atlantic usually at levels down to 1000ft or less in all weathers day or night, finishing with a practice homing and simulated attack on No.9 radar buoy moored off the north coast. Standard height for the attack was 300ft at night, and 100ft in daylight. Take off Runway 27, climb out, right turn over Lough Foyle with County Donegal to the left and Ben Twitch to the right. Cross the coast over Magilligan Strand with the Point under the left wingtip, steer for Inishtrahull Light and out over the Atlantic. Conditions aboard were noisy and uncomfortable, and on long flights over the sea things could become somewhat boring but the Shackleton, despite the lack of crew comfort, was a sturdy aircraft and proved to be a very good submarine hunter.

As the squadrons achieved their full complement of eight aircraft, they began to settle down to the normal peacetime routine of training sorties involving navigation exercises, bombing and gunnery practice, maritime surveillance and anti-submarine exercises, many of which involved detaching aircraft at other bases in the UK or much further afield. Search and rescue (SAR), carried out in rotation by individual crews at a time, was also a very important task. Certain detachments became a regular part of the squadron calendar, such as the 'Fair Isle' visit to Malta each year to exercise with the Royal Navy submarine squadron based there.

Much closer to home as far as the Ballykelly squadrons were concerned, was the annual three-week visit to JASS. This involved ground instruction in tactics and techniques, followed by theoretical exercises at HMS Sea Eagle, the naval shore establishment in Londonderry. The practical side would then follow involving ships, submarines and aircraft from NATO countries operating in the Northwest approaches. At the end of each phase all personnel would return to Sea Eagle, find out how well or badly they did and argue about the outcomes! The object of the exercise was to constantly develop and improve the techniques involved in the combined air/sea approach to anti-submarine warfare, vital as the Soviet Union was constantly improving and enlarging its submarine force. Of course there was a fair amount of light hearted banter at the same time- RAF aircrew were constantly amused by naval reference to 'going ashore' and 'waiting for the liberty boat' in reference to a shore establishment! Needless to say, the navy was not amused at this attempted mockery of deeply cherished naval custom.

Ground Support

An essential component in achieving maximum operational effectiveness was the engineering organisation supporting the squadrons. Aircraft were normally left out in the open on the airfield and minor servicing was carried out while the aircraft were at their squadron dispersal. Each of the operational squadrons possessed a T2 type hangar in which first line servicing at squadron level was carried out. A form of centralised servicing was adopted from the beginning whereby the Aircraft Servicing Flight (ASF), undertook both second line and deeper servicing of all systems on the Shackleton. The unit occupied Hangars 4 and 5, which were extended length T2 type. Because of the 120ft. wingspan of the Shackleton and the 100ft. maximum opening of the hangar doors, the aircraft had to be pushed in side-on, using low trolleys on rails embedded in the hangar floors. The tailwheel was mounted on a hand-pulled trolley and the whole assembly was then towed into the hangar by tractor or, on occasions, pulled by large amounts of manpower! At first, there were shortages of some spares, and it was commonplace to remove parts from one aircraft to keep another airworthy. One Mark 1 in particular, WB820, seemed to bear the brunt of this policy and apparently didn't fly for eighteen months after arrival at Ballykelly with 269 Sqn. Airtests usually followed a period of maintenance, and this was the opportunity for the long-suffering fitters and mechanics to go aloft for a short trip over the North coast.

A Third Squadron Forms

On 1 January 1954, the third and final Shackleton squadron at Ballykelly, No.204, was formed. By this time the mistake of equipping squadrons with both marks of Shackleton was being rectified, with 240 and 269 slowly relinquishing their Mark 2's as detailed below and standardising on the Mark 1, and 204 nominally being equipped with solely Mark 2's. In the event it wasn't quite as simple as that with the squadron only having four Mark 2's of its own on formation, along with a couple of Mark 1's, WB828, and VP284 which arrived in February. A further four Mark 2's WL790; WL738; WL747 and WL748 were borrowed from 240/269 Sqns., along with some Mark 1's. The situation was normalised in August when the squadron stopped using the earlier mark completely, and took on charge the four Mark 2's it had been borrowing.

Above, a Westland Dragonfly of Eglinton Station Flight overflies WB861/D of 240 Squadron at Ballykelly. The light slate grey letters were worn either side of the roundel, the squadron letter 'L' always to the rear. The protective shield has been removed from the scanner for the ASV13 radar under the nose. Photo per David Hill

The Locals Complain

With three fully equipped squadrons, JASS Flight and frequent visitors using the airfield at all hours of the day and night, Ballykelly had become a very busy station. Some indignation about the noise was expressed in the Chamber of Limavady Borough Council, with complaints of "low flying jets", and querying whether all this activity was necessary, after all "there isn't a war on". A diplomatically worded letter from the station CO no doubt helped to smooth things out.

Notable among the visitors to JASS at that time were Lancasters of the RCAF, whose appearance was immaculate, with a highly polished natural metal finish in stark contrast to the heavily exhaust-stained Shackletons painted white overall with medium sea grey upper surfaces. Code letters also appeared in medium sea grey.

Colours and Markings

In the early fifties, Coastal Command used a system of lettering allocated within the two coastal Groups to identify individual squadrons. A second letter to identify particular aircraft in a squadron then accompanied this. The positioning of these letters on the fuselage varied from unit to unit, but generally the squadron/unit code appeared towards the rear, and the individual letter towards the front of the aircraft. The individual letter was usually referred to as the hull letter, perpetuating the practice when all maritime squadrons were equipped with flying boats. Markings as applied to the Ballykelly units during 1952-1954 were as follows: -

No.240 Sqn.

Unit Code - L.

Hull Letters in the range A to H. These letters were positioned either side of the fuselage roundel, with the Unit letter to the rear.

No.269 Sqn.

Unit Code - B.

Hull letters in the range A to H and J. A different presentation was used in that the Unit letter was placed on the rear fuselage, just forward of the tailplane, with the individual letter on the nose, but very small and invisible from a distance.

JASS Flight.

Unit Code - G.

Hull letters were W;X;Y. Positioned on nose in standard size.

At this stage no squadron badges of any kind were carried although a newly delivered Mark 2, WL747, attending the Coronation Review at Odiham did carry what appeared to be a squadron crest on the nose. JASS Flight aircraft wore single black bands on the outer wings and mid-fuselage, which were unique.

At the time of 204's formation individual hull letters were starting to go out of fashion at Ballykelly, although unit letters continued to be worn. 204 Sqn. was allocated Unit Code 'T', and individual letters in the range R to Y. It's not clear whether the squadron ever actually used the letters on their aircraft.

Other Residents

Ballykelly also had on strength a Station Flight Anson, TX167, used for communication work between bases. Two other types were also present; an Airspeed Oxford, N4775, which was restored to airworthy condition after being discovered derelict when the station re-opened, and a Tiger Moth, DE574. The Oxford only lasted a short time before it was pushed back into a hangar and quietly forgotten about. The Tiger Moth was somewhat different and was in great demand, be it as the CO's personal mount or something to jump into and go up to Portrush Golf Club and buzz some colleagues! It unfortunately came to a sticky end when on one occasion the engine stalled on final approach, the aircraft landing in a tree and becoming rather bent.

In 1955 approval was given to start repainting the Shackletons gloss overall dark sea grey. This was felt necessary because of the difficulty in keeping the aircraft even moderately clean. The four Griffons and the two cabin heaters left heavy exhaust stains on the white paintwork, the new scheme didn't prevent the exhaust smoke, but at least it wasn't so obvious! It is rumoured that grey M/T paint was used initially at Ballykelly, but it was found that it peeled off after a very short time and the practice had to be abandoned!

Tragic Events

Although life at Ballykelly, for the younger members of the Shackletons' crew at least, allowed ample time for having a good time, the potential for tragedy was never far away. Within eighteen months of the first squadrons' arrival, two Shackletons had been lost with only one survivor from the two crashes. Less than two weeks after 240 had arrived at Ballykelly, the squadron detached five aircraft to Scampton to take part in Exercise Castanets in the North Sea. One of the aircraft VP261, actually on loan from 120 Sqn. at Aldergrove, which also had a detachment at Scampton for the exercise, crashed on 25 June 1952 off the Berwickshire coast while exercising with the submarine HMS Sirdar. The aircraft was captained by W/Cdr Bisdee, OC Flying at Ballykelly. Of the thirteen crew aboard, eleven died outright, with two persons being rescued by the submarine, which witnessed the impact through the periscope. One of the survivors died the following day.

On 11 December 1953, 240 Sqn. were to suffer a second fatal crash when WL746, a 269 aircraft on loan and captained by F/Lt Chevallier, failed to make a scheduled report shortly after concluding an exercise with a submarine. Later wreckage was found in the Sound of Mull, but no survivors from the crew of ten and the cause of the accident was never established. F/Lt Chevallier was a very popular member of a very happy squadron, having run the station model club and been instrumental in started up 240's squadron newsletter. It was a bleak time at Ballykelly, as within a few days of the crash a bus carrying civilian workers to the base was involved in a serious accident with several killed, and a Royal Navy Avenger from the neighbouring airfield at Eglinton crashed with the loss of the crew.

A potentially dangerous but fortunately less serious accident occurred at Ballykelly on 26 October 1954 when VP256, originally coded A of 269 Sqn., attempted to take off with the elevator locks engaged. The aircraft failed to get airborne and ended up off the end of the runway, eventually being categorised a write-off. There were no casualties.

Detachments

However, life had to continue and the chance of getting away on detachment to exotic locations provided some reward for enduring long, noisy hours and potentially hazardous conditions. Detachments to remote places all over the world were a feature of life in Coastal Command, and not only for the aircrews. Every Shackleton leaving for an extended period away from base took along an appropriate mix of groundcrew, plus a selection of spare bits and pieces. The capacious weapons bay could be used for storage of gear, although it was not unheard of during the Shackleton's career for the weapons bay doors to accidentally open in flight, depositing sundry items to the four winds. Some of the more notable detachments which took place in the early years included :-

June 1952

Operation Castanets - 240 Sqn. went to Scampton. Aircraft involved included WG507/E; WG509/G; WB860/C; WB859/B. - 269 Sqn. was based at Lann Bihoue, Lorient, France.

October 1952

Exercise Emigrant - 269 Sqn. sent six aircraft to the RCAF base at Greenwood, Nova Scotia

September 1952

Exercise Mainbrace - 240 Sqn. detached to Sola/Stavanger. Major NATO maritime exercise. Squadron involved in submarine searches. Aircraft involved included WB858/A; WB861/D; WG509/G.

September 1953

Exercise Mariner - Shackletons from both squadrons are believed to have been detached to Montijo, Lisbon for this major annual NATO exercise. Before leaving, the crews were informed that they would be the first British forces operating from Portugal since the Peninsular War! The ASF was under pressure to get as many aircraft as possible ready in time. The Station Flight Anson was also involved - it flew down to Lisbon loaded with spares and personnel, flying over the Pyrenees. On the return journey one of the long suffering Cheetahs gave up over the mountains and many items had to be jettisoned to lighten the load. They made it back to Ballykelly eventually, but had nothing to declare at Customs!

June 1955

Exercise Durbex II - 204 Sqn - Detachment to South Africa. Aircraft involved WL738; WL740; WL790; WL792. Left Ballykelly on 14 June, route Idris - Khartoum - Nairobi - Durban, arriving on 19 June, total flying time 33 hours. Started return journey on 5 July, routing via Accra instead of Khartoum, arriving back at Ballykelly on 10 July, total flying time 43 hours 10 mins. Due to the unserviceability of one aircraft at Nairobi, a fifth was sent out from Ballykelly. The exercise only lasted three days!

September 1955

Operation Cooks Tour - 240 Sqn - This detachment involved Photographic and other survey work of a number of islands in the Line Islands group in the central Pacific Ocean to ascertain their suitability to support atomic tests in the area. Three aircraft left Ballykelly routeing via Goose Bay - Winnipeg -Vancouver - Honolulu - Canton Island in the Phoenix Island group, west of the Line Islands. One aircraft, WB860, suffered an engine failure and was delayed at Canton Island until a spare engine was flown out in WG507. Once repaired, WB860 continued its journey westabout via Fiji - Townsville - Darwin - Singapore - Negombo - Habbaniya - Luqa - Aldergrove (customs clearance) - Ballykelly. The crew (Captain Flt. Lt. Bill Williams), were met by the station commander and a party from Command HQ and informed that they were the first operational crew to circumnavigate the globe.

New Challenges

During the first three years of Shackleton operations there had been triumph and tragedy; difficulties with a shortage of spare parts had largely been overcome, and living conditions, while not luxurious, had certainly improved. Two crews had been lost in accidents, and most others had experienced in-flight emergencies of one sort or another. The established pattern of operations would continue with new challenges ahead.

PART 3 - WORLDWIDE DEPLOYMENTS (1956-1958)

As the mid-fifties approached the work that the UK had been undertaking in the development of thermonuclear weapons was getting to the stage where a number of devices would have to be exploded in a series of test programmes. The work carried out by the 240 Sqn. detachment in September 1955 helped to decide which Pacific island would have the dubious distinction of hosting the live tests. Elsewhere trouble was brewing which would necessitate UK military intervention, and all these events would have an impact on the operational tasks of the Ballykelly squadrons in one way or another. However, the normal duties of the maritime squadrons would have to be carried out as well, which would make for a busy time.

New Style Markings

In 1956 the markings worn by Shackletons at Ballykelly, in common with those at other stations, underwent a revision. Aircraft were now standardised on the overall dark sea grey scheme, with only a white squadron code on the rear fuselage. However, this arrangement was altered twice in quick succession; first the unit letter being repainted in red outlined in white, and secondly the unit letter being dropped in favour of the squadron number, also in red outlined in white, positioned on the rear fuselage. The individual letter was placed on the nose, again in red and white. At Ballykelly they decided to be different and dropped the use of the nose letter altogether, although squadron insignia started to appear on the noses as follows: -

204 - A dark grey cormorant standing on a mooring buoy in a white shield.

240 - A winged helmeton a rectangular white background.

269 - The squadron crest of a sailing ship in full sail in a white disc.

JASS Flt - No badge was carried but, as mentioned earlier, black fuselage and wing bands were carried.

Many of the aircraft also carried crew captain's name below the badges.

Above - a 1957 shot of VP287 of 269 Squadron, taken at Bovingdon. The Shackletons based at Ballykelly, unlike all other Shackleton units, did not use individual aircraft hull letters until 1960. No 269, in common with 204 and 240, paced a squadron crest/badge in place of the aircraft letter, often with the crew captain's name somewhere on the nose, in this case F/Sgt WH Cowey. NumberOne Props are not dressed properly, because the engine was broken. Photo per David Hill.

Equipment Updates

Throughout their period of service Shackletons were continually receiving updates or additions to the fittings and equipment. Three major update programmes would eventually take place, but at this stage, only piecemeal changes had occurred. Notable among these was a search and rescue aid, SARAH (Search And Rescue Automatic Homing), which started to become available in 1956 although the equipment wasn't fitted to Shackletons until the late fifties, and not at all to the Mark 1. H-shaped aerials positioned on either side of the nose and selected alternately every six seconds, received a signal from a transmitter in the lifejacket of a downed airman. Although of help, the location of small objects in a rough sea was still largely down to good visual coverage and good luck.

Another fitment, in the mid-fifties, was Autolycus. This device was intended to be able pick up the diesel exhaust fumes from a submerged submarine using its snort. The obvious difficulty was distinguishing submarine fumes from those of any other vessel, and its options for effective use operationally were limited, although an improved and highly effective version did appear in the mid-sixties.

Both marks of Shackleton had been delivered with a dorsal gun turret housing two 20mm Hispano cannon, the Mark 2 having a further twin installation in the nose. While the nose guns were to remain fitted right up to the aircraft's withdrawal from maritime service, the dorsal turrets were removed progressively from 1956.

Demise of JASS Flight

At the beginning of 1955, JASS Flight replaced their Mark 1s with three new Mark 2s. As no other Shackletons at Ballykelly carried hull letters at this time, the unit had the choice of the whole alphabet and settled on the following - WR969/A; WR967/B; WR966/C. The unit code G was carried initially, but was removed when Coastal Command altered its policy on squadron letters in 1956. Unfortunately, the unit's life was to be short, at the beginning of March 1957 it was disbanded, WR966 and WR969 being delivered to No.220 Sqn. at St.Eval by crews from 204 Sqn. on 6 March, with WR967 going to No 42 Sqn. also at St.Eval four days earlier.

Exercise Encompass

Over the Christmas period 1955, an upsurge in terrorist activity by EOKA in Cyprus led to a decision to dispatch additional troops to the island to counter the threat Shackletons from most UK squadrons were ordered to transport the troops, while Hastings' were to carry the heavy equipment. A number of crews and aircraft from all three squadrons at Ballykelly were involved firstly carrying troops from Lyneham to Luqa, and then flying shuttles between Luqa and Nicosia in the first available aircraft of whatever squadron. Generally thirty-three fully equipped troops could be carried in some discomfort in every available space in the aircraft, the time taken for the flight from the UK to Malta being some eight and a half hours. To allow as many troops as possible to be accommodated, a reduced crew of five, two pilots, navigator, flight engineer and signaller, was used. The operation ended on 24 January 1956, the whole episode demonstrating a further use for the Shackleton in an operational setting, that of troop transport.

Operation Mosaic

No sooner had the operation to transport the troops to Cyprus been completed, than 269 Sqn. started to prepare for a major detachment in support of UK atomic testing on Monte Bello Island, off the NW coast of Australia. Four specially modified aircraft, including VP255 and WB820, left Ballykelly on 18 February. Each crew comprised an additional member, a meteorological observer, and the purpose of the operation was to obtain weather information in the Timor Sea. The aircraft routed Ballykelly - Idris - Habbaniya - Karachi - Negombo(Ceylon) - Changi - Darwin. Meteorological sorties were flown from Darwin until 25 June, when all four aircraft flew down to Melbourne and finally Sydney. On 2 July a four-ship formation overflew the Sydney Harbour Bridge, before starting the long journey home, arriving on 11 July.

Yet More Tasks

One of the methods of gathering data for weather forecasting in the UK was by means of Ocean Weather Ships moored at set locations in the North Atlantic Ocean. The crews of these converted frigates led a lonely and uncomfortable existence bobbing up and down in an invariably lively sea. Shackleton crews were in the habit of using these ships for homing practice or waypoints in a navigational exercise, and one task they were delighted to perform was the dropping of Christmas goodies to the ship at Station Juliet a few days before the festive season, a commitment which endured until the ship's withdrawal in the sixties.

During the fifties, progress in commercial air travel allowed members of the Royal Family to travel routinely by air across the Atlantic. However, it was still considered necessary to escort the royal aircraft across the miles of ocean. The usual arrangement was for the RCAF to provide the escort over the western half of the Atlantic, with the RAF taking over in mid ocean. Two aircraft were involved, one flying ahead and one behind and the Ballykelly squadrons frequently were tasked with these missions. On occasions it was necessary to travel further afield, as on 15 October 1956, when 204 Squadron sent WL738 and WL740 to cover HRH the Duke of Edinburgh flying from Gibraltar to Kano, Nigeria. One drawback was the relatively slow speed of the Shackleton compared to the current airliners of the day, such as the Stratocruiser and Constellation. On occasion Shackletons were called out on SAR to escort transatlantic airliners, which had had to shut down one engine for one reason or another. Even with three engines a Constellation could generally outpace a Shackleton with four, which could be somewhat embarrassing!

Disaster Strikes

During October 1956, No.36 Sqn. flying Neptune MR 1's and based at Topcliffe, took seven aircraft to Ballykelly on their annual visit to JASS. On 10 October, WX545 took off on a local Jassex and during the course of the sortie flew into a hillside on the Mull of Kintyre, with all nine crew being killed.

Operation Challenger

Challenger was the code name for the operation, which transported thousands of troops from the UK to Cyprus via Malta who were involved in the Suez Campaign during October/November 1956. Similar arrangements were put in place as in Operation Encompass earlier in the year, with Shackletons from many home-based units shuttling loads of thirty-three fully equipped soldiers from Lyneham to Luqa and on to Nicosia. The operation started for the Ballykelly squadrons at the beginning of November and was completed just before Christmas.

Operation Grapple

Partly as a result of 240's survey work, which had been carried out in August 1955, Christmas Island in the South Pacific was chosen as the site for testing British thermonuclear weapons in a phased programme, which lasted two and a half years. Shackleton squadrons were involved in every phase in roles which included patrolling of the prohibited areas, meteorological reconnaissance, SAR and casualty evacuation, and regular transport shuttle between Christmas Island and Honolulu. After an initial detachment by two aircraft of No.206 Sqn. from St.Eval during the period of the setting up of facilities (Grapple Phase I), all three Ballykelly squadrons bore the brunt of the work until the completion of the tests in late 1958. Aircraft participating in Grapple wore special markings consisting of a large red frigate bird clutching a grappling hook placed above the fin flash, which was replaced by a Union Jack outlined in white. Also a white top to the fuselage, originally intended to be introduced only on Shackletons based overseas, was applied to all aircraft by mid-1958. Ballykelly involvement was as follows:-

Above - WB859 warming up at RNAS Eglinton 'At Home', 19th July 1958. This aircraft had been detached to Christmas Island with 240, leaving Ballykelly on 26th March 1958 and returning by 3rd June. Just visible on the fin is the Union Jack, which replaced the fin-flash for the detachment. Above this was painted a red frigate bird was positioned holding a grappling hook in its claws. The winged helmet squadron badge on a white square is on the nose. Photo via David Hill

February 1957

240 Sqn. detached to Christmas Island for Grapple Phase II.

On 26/27 February the first aircraft departed Ballykelly routeing Lajes, Azores - Kindley Field, Bermuda - Charleston AFB, South Carolina - Biggs AFB, Texas - Travis AFB, California - Hickham AFB, Hawaii - Christmas Island. Total flying time approximately 42 hours. Further aircraft followed in March.

Aircraft which received special mods at 49 MU, Colerne and were probably involved in the detachment were WB835; WB856; WB860; WB861; WG507; WG509 and possibly WB859. Conditions on the island were basic but adequate and there were the obvious attractions of a typical South Pacific island. Accompanying the aircraft was a contingent of squadron support and maintenance personnel, who travelled out in the Shackletons. Three thermonuclear devices were dropped by Valiants on 15 and 31 May and 19 June, and the detachment had returned home, using the same route as the outward journey, by 4 July.

March 1958

240 Sqn. again to Christmas Island for Grapple Y.

Aircraft involved WB823; WB826; WB828; WB859; WB860; WG507; WG509 Left Ballykelly on 26 March. Nuclear bomb dropped on 28 April. Detachment returned to Ballykelly on 3 June.

May 1958

204 Sqn. took over from 240, as Grapple Y graduated into Grapple Z.

The squadron replaced its Mark 2 aircraft with Mark 1's, reckoned to be more suitable for the task. These were VP263; VP266; WB828; WB850; WB856 and WB857. All these aircraft were previously on the strength of either 240 or 269 Sqns and were modified for operations from Christmas Island. The main body of the squadron left for home during July, leaving a couple of aircraft behind to operate alongside 269 when they arrived.

July 1958

269 Sqn. made their first trip to Christmas Island in support of 204 in Grapple Z, the first aircraft leaving Ballykelly on 14 July and routeing westwards as before. Similar duties were performed as on previous detachments, and this major movement of aircraft and personnel halfway across the world was becoming pretty routine for the Ballykelly squadrons. The series of tests were now coming to a close and two final drops from Valiants were made on 2 and 11 September. Aircraft used by 269 on the detachment consisted of VP265; VP289; VP294; WB826; WB835; WB860 and WB857, which was left behind by 204. An unusual request to 269 arose during this time when a casualty injured in a road traffic accident needed to be airlifted to Honolulu for specialist treatment. Although a large aircraft, the Shackleton has a fairly small entry door on the rear starboard fuselage. Quite a bit of imaginative thinking was required to figure out a way of easing the stretcher and the seriously injured patient through the door and inside the aircraft. It was finally achieved and the patient duly flown to Honolulu and, having survived an attempt by the Americans at delousing the aircraft interior with everybody inside subsequently made a complete recovery! All aircraft had returned home by early October.

So ended Operation Grapple. A commitment for the Shackleton squadrons of the utmost national importance had been successfully completed. But these weapons drops were not the only bomb tests being supported by Ballykelly's squadrons.

Operation Antler

No.204 Sqn. was selected to cover a further series of tests, that of atomic weapons, at Maralinga in central Australia. A detachment left in August 1957 and was based at RAAF Pearce, W. Australia, flying meteorological reconnaissance sorties. Aircraft involved were WL739; WL748 and WL795. The detachment had ended by November.

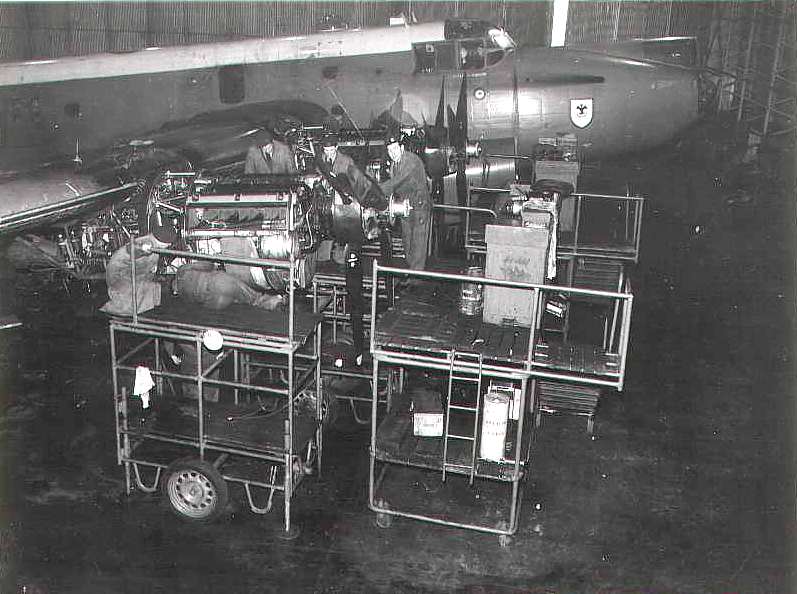

Above - A scene from one of the ASF hangars, Ballykelly, March 1958. The unidentified aircraft from 204 Squadron sports a RAAF roundel below the cockpit window, indicating that it probably took part in the squadron's detachment to RAAF Pearce, Western Australia, August-November 1957. The purpose was to undertake meteorological sorties in support of Atomic weapons testing at Marralinga under the codename Operation Antler. This narrows down the identity of the aircraft to either WL739; WL748 or WL795. Also of interest, and which could solve the problem is the name 'F/L FH Chandler' under the co-pilot's window. Many years later, on 7th October 1971, a 204 Sqn Shackleton, then based at Honington and piloted by F/L Bill Houldsworth, scattered the ashes of the late Frank Chandler off the Donegal coast. Frank died aged 48 and had requested this be done at the place where he had begun so many Atlantic patrols when based at Ballykelly. Photo per David Hill

The Home Front

While all these comings and goings were taking place, life carried on at Ballykelly with participation in various exercises, as well as JASS courses and Fair Isle detachments. Notable was Exercise Strikeback in September 1957. This was a large NATO exercise comprising Orange and Blue Forces, which in its various phases stretched from Jan Mayen Land in the north to Portugal in the south. 204 Sqn., part of the reconnaissance element of the Orange Force, sent three aircraft to Kinloss including WL738 and WL740 and flew patrols up to near Jan Mayen Island. 269 Sqn. went in its entirety to Wick, the detachment being notable for an eight aircraft scramble at 0630 on 19 September at the start of he exercise.

Two SAR escorts for Royal flights were flown by 204 Sqn. during 1957, one on 29 May and the other, an escort to HM the Queen going on a visit to the USA and Canada, flown in WL744. On 1 September 1958, ASWDU moved back to Ballykelly from St. Mawgan after an absence of more than seven years, bringing with it nominally three aircraft. The unit tended to chop and change its aircraft depending on what trials were being conducted, and over the next couple of years would use examples of both early marks of Shackleton. One of the most important tasks being undertaken around the time of the move was the operational evaluation of ECM equipment, known as Orange Harvest, which would become part of the phase II package of improvements. More about the unit later.

Revised Squadron Numberplates

As the Grapple commitment was coming to an end, changes to the squadron numberplates were introduced at Ballykelly. In order to perpetuate the identity of more senior squadrons, No.269 was re-numbered 210, and No.240 became 203. Coinciding with these changes, re-equipment of the squadrons was also underway, including the arrival of the latest version of the Shackleton - the Mark 3.

PART 4 - RAPID ADVANCES (1959-1963)

By the end of 1958 the Shackleton, in both variants, had been in service for more than seven years and a number of shortcomings had become apparent. An improvement on the earlier marks had been in the planning and design stage for quite a protracted period, in fact since shortly after the Mark 2 entered service. This was originally designated the Mark 2A eventually becoming the Mark 3, and was intended to overcome the deficiencies in range and endurance the earlier marks had exhibited in operational service as opposed to that envisaged at the design stage. However, the promised performance again proved elusive, due mainly to the heavier overall weight of the new model, which led to delays in the placing of production orders. Eventually these were placed and the new aircraft, albeit slowly, started to come off the production lines at Avro's Woodford plant in Cheshire. The main external differences between the Mark 3 and earlier versions were a tricycle undercarriage and wingtip fuel tanks. Internal changes were mainly aimed at enhancing the working environment for the crew, with the navigationaland other operational equipment being similar to the Mark 2 then in service. Although the Mark 3 was a new airframe and was to be considered a different aircraft type to the Mark 2, their main role was the same. Technology was advancing at an ever increasing rate, and to remain effective against the new generation of submarines which were coming into service at the time, the same new and updated equipment would have to be installed in both types. This would eventually be carried out in three distinct phases over six year period.

The Mark 3 Arrives

Above - Mk 3 XF706 of 203 Sqn. This aircraft served with the squadron as a basic Mk 3 for a year from December 1958. Several non-standard features are apparent which were typical of 203 at this time: smaller than normal squadron number; no hull letter, and a small seahorse squadron badge on the nose placed over a crew captain's name. The Union Jack denotes an overseas detachment, possibly to Norfolk, Virginia for Exercise Fishplay IV, for which 203 sent five aircraft in September 1959. Photo via David Hill

Not only did 240 Sqn. suffer the trauma of renumbering, they were also faced with the not inconsiderable task of getting to grips with this latest version of the Shackleton. The Mark 3 had first entered squadron service with No.220 Sqn. at St. Mawgan in August 1957, some two years late. Deliveries to other squadrons followed and 203 received their first examples in November 1958. By the end of the year the following had been taken on charge:- WR974; XF702; XF703; XF704, and XF705, with WR973 arriving in February 1959. The XF series aircraft were brand new basic Mark 3's, while WR973 and WR974, being among the first of their mark to be completed and therefore more than two years old, were already modified to Phase 1 standard when they arrived at Ballykelly. Phase 1 introduced an improved search radar, the ASV Mk.21, ILS, VHF homer, the Mark 5 radio altimeter, doppler navigator and Mark 10 autopilot. A flame float dispenser was also fitted in the port beam. The Mark 3 had a difficult introduction into service, and even by the time 203 received their aircraft, problems with the engines and undercarriage were still occurring.

The remaining Mark 1 aircraft which had been inherited from 240 were quickly dispensed with, the last four WB859; WB860; WG507 and WG509 having served the squadron faithfully since formation in 1952. Three went to 23MU for open storage and eventual scrapping, while WB860 soldiered on with 204 Sqn. for a further year before suffering a similar fate.

Squadron establishment was now reduced from eight aircraft to six in Coastal Command, reflecting a belief that fewer maritime aircraft would be required in future, and also of course, saving money! The detrimental effects of this reduction were to be felt later when aircraft were being withdrawn from the squadrons in considerable numbers to undergo the various equipment updates, and a shortage of available aircraft was experienced in trying to meet pressing needs all over the world.

Ballykelly's policy of not applying individual hull letters was still in force at the time of the Mark 3's introduction. To go even further, 203's squadron number on the rear fuselage was presented smaller than standard. They did, however, include a small seahorse from the squadron crest on the nose, with crew captain's name below on at least some of their aircraft.

Canadian Misadventure

On 17 August 1959, one of 203's aircraft, WR974, left Ballykelly to fly to the RCAF base at Greenwood, Nova Scotia. Because of bad weather at Greenwood, the aircraft was diverted to the RCN base at Dartmouth. The weather wasn't particularly good there either and the aircraft landed too far down the wet runway and could not stop in time on the rather short distance available. To avoid going off the end of the runway the pilot retracted the undercarriage and WR974 came to a halt, fortunately with no injuries. Severe damage was caused, this being repaired at Dartmouth by Fairey Aviation of Canada, with the aircraft finally returning to Ballykelly in August 1960, somewhat later than planned!

On the 23rd September, 203 took the remainder of their aircraft to the NAS Norfolk, Virginia to take part in Exercise Fish play IV, returning some three weeks later.

Demise of the Mark 1

While 203 Sqn. were experiencing the joys of the Mark 3, the other squadrons at Ballykelly were also changing their complements of aircraft, although the change for them was perhaps less problematic. As the new decade approached, a process of continual movement of aircraft, both Mark 2's and 3's, would occur as aircraft went either to Avro's or a Maintenance Unit for update. The Mark 1 had come to the end of its operational career, but would continue in a training role for a few more years.

At the end of Operation Grapple 204 Sqn. had Mark 1's on strength, having been specially equipped for the occasion. During 1959 the squadron reverted to the Mark 2, the first two, WL745 and WL793, arriving in July 1959. These were already Phase 1 modified, as were subsequent deliveries to the squadron, WL797; WR951 and WR957. The exceptions were WR962, which spent a month with 204 from June 1959 and WR955, with the squadron for a year from October 1959, which were basic Mark 2's.

The first Mark 1 to go was WB848 in January 1958, and the last, WB860 departed to 23MU in March 1960, leaving ASWDU as the only unit at Ballykelly using the occasional example for trials work.

WL751/N of 204 Squadron running up the engines beside the squadron dispersal. This aircraft was with the squadron from June 1960 to June 1961 as a Phase I modified example. By this time the Ballykelly squadrons had come into line in terms of adhering to normal Coastal Command markings, most obvious of which was the adding of an individual hull letter on the nose. The spire of the Ballykelly Parish Church is visible above the outer left engine. Photo David Hill.

269 Re-Equips with the Mark 2

Meanwhile over on the north side of the main runway near the 03 threshold of the minor runway, 269 Sqn. were getting used to the later version of the type. The squadron had been partially equipped with the Mark 2 back in 1953, when mixed version units were in vogue, but had quickly passed them on when the difficulties in operating the two types side by side were realised. Shortly before 269 Sqn. was renumbered 210, five Mark 2's had been delivered to the unit, WL748; WL750; WL790; WL795 and WR956. A sixth, WR955, arrived in February 1959, which brought the squadron up to full strength. At this stage none of the squadron aircraft carried hull letters, just the squadron number on the rear fuselage and a squadron badge on the nose.

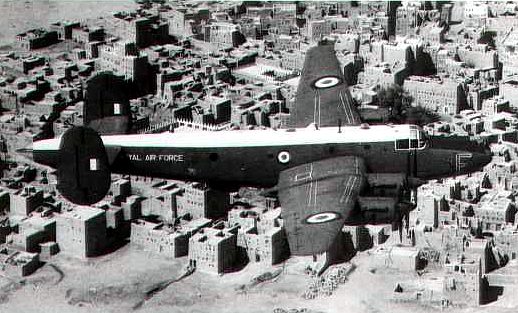

The squadron was the first at Ballykelly to be earmarked for a possible colonial policing(COLPOL) detachment. While Ballykelly's aircraft were involved in the nuclear weapons detachments, other Shackleton squadrons were operating from a number of Middle East locations against rebel tribesmen in the Aden Protectorate and Oman. In preparation for a possible detachment to the Middle East, 210 sent three aircraft to Idris, Libya in March 1959 for training, with the rest of the squadron following a few weeks later. In the event the squadron was not needed for this additional role.

Mark 2 Modernisation

As with the Mark 3, the earlier Mark 2 was similarly being updated to Phase I standard. At the time of the squadron re-numberings all Mark 2's were basic unmodernised examples. But by 1958, aircraft were being withdrawn from squadron service and sent to either Avro's or 49MU for update, which took, on average, about a year. These were eagerly awaited because of, among other things, the ASV21 radar, which promised big improvements over the old and rather unreliable ASV13. A specially modified Mark 1 aircraft belonging to ASWDU had toured Shackleton bases during the second half of 1958 to give a preview of the new equipment and provide some instruction. As already mentioned, 203 received one Phase I modified aircraft at the time of their re-numbering, but a few months were to follow before the other two squadrons swopped their basic aircraft for the updated version. No.210 Sqn. got their first, WG555, in April 1959, while 204 received two simultaneously in July, WL745 and WL793. As more Phase I modified aircraft became available, so each squadron's entire complement would change, and this was only the start of the modernisation programme!

Re-equipment was complete in all three squadrons when WL748 arrived for 210 Sqn. in January 1961, although XF703 was delivered to 203 in May 1961, having previously served with 120 Sqn. as a Phase I

WL797/Y of 210 Sqn, as a Phase II modified aircraft. Official records seem to imply that this aircraft was only modified after it left 210 prior to it going to 42 Sqn. In the background a freight train is passing along the railway line to Londonderry which at one point crossed the main runway. Photo via David Hill.

Hull Letters At Last

The Ballykelly squadrons had been unique among Shackleton units in not applying hull letters to their aircraft during the period 1954-1959. However, this was about to change. Towards the end of 1959 hull letters, applied in the standard Coastal Command pattern, started to appear on the noses of aircraft of all the units based at Ballykelly. The letters were allocated on a station basis i.e. letters weren't repeated on the base, and each unit had its own sequential allocation. These were: -

ASWDU - A and B

203 Sqn. - E to L (except I)

204 Sqn. - M to R

210 Sqn. - T to Z

With a squadron complement now down to six aircraft, it can be seen that not all letters were taken up at any one time.

For a short time after the introduction of station letters, 203 persisted with their seahorse badge on the nose, but by the time the Phase I modified had been delivered, this practice had been discontinued. The seahorse made a brief reappearance in 1965 on the fin prior to the removal of squadron markings due to centralised servicing. Just to be different, 204 Sqn. moved their cormorant badge in a shield to the tail fin above the finflash to start with, alternating between that position and a squadron crest on the nose up to the time squadron markings were removed. No. 210 Sqn. didn't apply any insignia at first but by early 1960 had the griffin from the squadron crest in a white disc on the nose beneath the cockpit, this position remaining unchanged until the general removal of squadron insignia. ASWDU hand painted the unit badge on a pre sprayed dural panel and rivetted onto the nose just forward of the captain's window of their two aircraft. By 1962, coloured spinners were also introduced, this period being the most colourful in terms of squadron marking at Ballykelly.

Squadron allocation was as follows:-

ASWDU - pale blue (50/50 ground equipment blue and white)

203 - roundel blue on the Mark 2

204 - Red

210 - dark green

In 1961 the squadron number was reduced in size and moved to a position above the scanner installation. The roundel was also made smaller and positioned just above and behind the wing trailing edge. The title 'ROYAL AIR FORCE' was introduced on the rear fuselage, just below and forward of the tailplane.

210 Sqn Near Misses

Not long after 269 Sqn. transitioned into 210, a bizarre incident occurred at the squadron dispersal. A decision had been taken to dispose of a quantity of time-expired World War II depth charges, which had been stored in Ballykelly's bomb dump since the end of the war. The chosen method of disposal was to load them onto Shackletons and quietly dump them at sea. Prior to loading they had been made safe, but some consternation had been caused when the first of the depth charges to be dropped had exploded on impact with the sea. On 26 May 1959 a crew from 210 were detailed to transport a further batch for dumping. All went well with a full load of twelve 250lb. devices duly loaded aboard a Shackleton parked at 210's dispersal area. The crew were quietly engaged with last minute tasks before boarding the aircraft prior to take off when the unthinkable happened, the complete load of depth charges were released onto the tarmac of the dispersal and started rolling about and bumping into each other! The unexpected explosion of the depth charges on the previous occasion sprang immediately to the minds of the crew members standing close by, and some record sprinting performances were recorded by some most unlikely people in an effort to put as much distance as possible between crew and a potential massive detonation! Fortunately no explosion took place; the depth charges were safely rounded up and successfully disposed of the following day.

Another potentially catastrophic incident befell another 210 Sqn. crew on 20 October 1961 when one of the squadron's Phase II aircraft, WR968, crashed on landing. A three engined approach and landing went wrong and the aircraft left the runway and caught fire. The crew evacuated in double quick time, and although the aircraft was burnt out there were no serious injuries. Provided nobody gets hurt these incidents usually have their funny side and no doubt get embellished as time goes by. A similar occurrence, at night and in poor weather conditions is another example

...there was a standing order that during local flying the galley on the aircraft was not to be used. On this occasion a 204 Sqn. crew was getting in some landings in driving rain when the aircraft slewed off the runway and got bogged down in the soft grass. As it came to a halt the first priority was not to immediately abandon the aircraft, but to cover up signs of hot soup being prepared in the galley, which by then had spread over a good deal of the floors and walls!

Enter the Phase II

The second stage of the Shackleton's continuing update programme got underway before all planned aircraft had gone through the Phase I mods and had been delivered back to the squadrons. Among modifications included in the Phase II package were: -

- Orange Harvest ECM equipment, easily identified by the plinth for the aerial head situated on the top of the fuselage. The aerial itself was heavy and caused problems with drag, and was rarely seen fitted to Phase II aircraft unless the equipment was to be specifically used

- Introduction of Mark 1c Sonics System, which allowed the deployment of active sonobuoys in addition to the passive variety

- UHF Radio Equipment

- UHF Radio Homer, which had smaller more rigid aerials on the nose

- TACAN

- Improved Radio Compass, which had a recessed aerial just behind the cockpit roof

- HF Aerial posts made more substantial and moved further back on the top of the fuselage

- Mark 2 aircraft were supposed to receive the engine exhaust system of the Mark 3, although in many cases this was retrofitted some time later.

The period of time that aircraft were at Maintenance Units or Avro facilities undergoing Phase II mods varied according to how complete the Phase I fitment had been, but on average took 8-10 months. No. 210 Sqn. received their first three during February/March 1961, WL787; WL791 and WR968. The first Phase II for 204 arrived in March 1961 (WR964), and the unit had five on strength by June.

203's Phase II's

203 Sqn's progression to Phase II's was a little more complicated. The unit received its first Phase II (WR988), in August 1961 and sent two (WR984/H and WR973/E) for modification, getting them back towards the end of 1961, at which time WR984 was recoded J. However, they were only destined to receive three Mark 3 Phase II aircraft before it was decided, because of a shortage of Mark 3's due to the modification programme, to re-equip the squadron with Mark 2 Phase II's. The first, WR965/J(later K), arrived in April 1962, followed by WL800/E; WL742/H; WL750/F; WL753/G and WR957/J. Immediately after re-equipment the squadron was involved in two exercises, Strong Gale and Cold Road, operating off Norway up to Bear Island and Spitzbergen, using Bodo as a base.

For the first time the squadrons at Ballykelly were now standardised on the one mark of Shackleton, and eventually all aircraft would be modified up to Phase II standard.

ASWDU - A Law Unto Itself?

As already mentioned, ASWDU had returned to Ballykelly in September 1958, occupying buildings and two dispersal pans in the centre of the airfield near the southern end of the disused runway. The unit was different from the others at Ballykelly and worked very hard at trying to maintain those differences. First of all, it reported directly to Coastal Command Headquarters at Northwood and not to 18 Group like the operational squadrons. This meant that it was a lodger unit and could operate in relative isolation from the rest of the station – no orderly duties, no SAR requirement, and for the erks no Gale and Crash Crew duty, a dreadful week long stint which included turning aircraft into the wind at all hours of the day and night. The unit could also find that it had to be unavoidably away at times of great upheaval, such as the presentation of squadron standards by Princess Margaret!

With two aircraft of its own, the unit comprised six or seven pilots and the same number of navigators. The numbers of signallers/AEOps were probably less than in an equivalent operational crew. All aircrew were probably a bit older than average and most highly experienced, all the pilots generally being qualified crew captains. Much time was spent away from base in the course of trials work, Malta and Bodo being popular for hot and cold trials work respectively. Close ties through regular visits were maintained with equivalent organisations in the US Navy, VX-1 at NAS Key West, and in the RCAF, the Maritime Proving and Evaluation Unit at Summerside. Indeed, more often than not, aircrew from these units were on exchange posting with ASWDU, and vice versa.

Because of its relative isolation from other units on the station, a number of extra-curricular activities are reported to have sprung up at various times during the unit's existence, including rabbit breeding, cattle dealing and car re-spraying to name but a few! Also, it always seemed necessary to do a navex to Gibraltar just before Christmas so as to replenish spirits stocks, although no doubt the other squadrons on the station had cottoned on to this one. Some day the full, unabridged story will be told of the unit and the remarkable individuals who so successfully ran these enterprises.

WR957/J of 203 Sqn probably taken shortly before squadron insignia was removed from the Ballykelly squadron aircraft. This progressively occurred from around the second half of 1965 into 1966 and was brought about in part by the need for squadrons to use any available aircraft on the station while some of their own were away on detachment, particularly the detachment to Changi during the Indonesian Confrontation from September 1964-January 1966. Photo via David Hill.

Early Sixties Detachments

As the new decade approached, Ballykelly's squadrons continued to be sent to far flung corners of the world, both on operational and goodwill visits. Some of the highlights were:-

April 1960

Exercise Sea Lion. Two aircraft from 210 Sqn. left on 25 April for Singapore to take part in this SEATO exercise. Aircraft involved were WR963/Z and WR969/Y. On the way home the aircraft joined up with other squadron aircraft at Idris, where they were on further medium level bombing practice in preparation for possible COLPOL detachment.

July 1960

Calypso Stream. Four aircraft from 204 Sqn. were involved in this goodwill tour of the Caribbean. The aircraft, WL745/M; WL751/N; WL793/O and WL797/P left Ballykelly on 11 July, routeing via Lajes, Azores and visiting Kindley Field, Bermuda; Palisadoes, Jamaica; Piarco, Trinidad and Stanley Field, British Honduras. The squadron got in some trooping practice with each aircraft carrying 29 troops from Trinidad to British Honduras as part of a troop rotation to the threatened territory. The aircraft also flew along the border with Guatemala in an effort to deter any thoughts of aggression from across the border. Returned to Ballykelly on 2 August.

September 1960

Exercise Fallex 60. 204 Sqn. were involved in this major NATO exercise. Not strictly a detachment, although the squadron operated from Kinloss at various stages, as part of the Orange reconnaissance force. Aircraft had an orange band painted on the rear fuselage, including WL751/N and WL793/O.

November 1960

Capex 60. 203 Sqn. sent three aircraft to Cape Town for the anti-submarine phase of this exercise, operating alongside No. 35 Sqn. SAAF, also a Shackleton unit.

February 1961

Jetex 61. This Indian Ocean exercise involved four aircraft of 204 Sqn. Detachment (WG558/P; WL745/M; WL751/N and WL793/O), left Ballykelly on 20 February, routeing Luqa - El Adem - Khormaksar - Katunayake, Ceylon. On the return leg flew from Khormaksar to Nairobi, and continued across to Kano, Nigeria - Idris - Ballykelly, arriving home on 20 March.

June 1961

Exercise Fairwind VI All squadrons were engaged in this major exercise. Several aircraft were based at Kinloss for the duration.

October 1961

Emergency deployment to the Caribbean. A two-aircraft detachment, (one each from 204 and 210 Sqns.) went out to Jamaica to support 42 Sqn. in relief operations in the aftermath of Hurricane 'Hattie'. Belize City, British Honduras was devastated in the hurricane, and the aircraft flew troops and emergency supplies from Jamaica to Stanley Field. The operation gradually wound down, with the Ballykelly aircraft being released in early December. The ruggedness of the Shackleton allowed it to operate under the prevailing primitive conditions which defeated the RAF's dedicated transport types.

February 1962

Further emergency deployment to the Caribbean. Riots in British Guiana had paralysed the country, and 204 Sqn. were again ordered to Jamaica to fly in supplies to Georgetown, as the docks were strikebound. The aircraft flew out on 19 February via Lajes and Bermuda. This was an open ended detachment expected to last 7-10 days, but eventually went on for five weeks. Due to the urgency of the operation, 204 had to borrow two aircraft from 210, and the aircraft involved were: - WG555/N; WR966/O, with WL748/X and WL787/T being supplied by 210. Daily flights were flown from Jamaica to Georgetown, this being yet another use for the Shackleton! A welcome return to Ballykelly was made on 23 March.

April 1962

Exercise Blue Water. No.210 Sqn. again sent two aircraft to the Far East to take part in the annual SEATO exercise. Based at Butterworth, Malaya.

June 1962

Exercise Fairwind VII. Seven aircraft of 204/210 Sqns. were detached to Kinloss for this major NATO exercise.

June 1962

COLPOL Training. 210 were on the move again, this time to Khormaksar for yet more internal security training, a task they were destined never to fulfil operationally.

Ballykelly Station Flight

During the early sixties, two aircraft were part of Ballykelly's Station Flight. A Vickers Varsity, WF331, was used for movement of stores to and from bases in England and occasionally further afield. A Hunting Pembroke, WV739, was utilised on communications duties and various personnel transport tasks. Another aircraft, Shackleton WG558, was delivered to Ballykelly after Phase II conversion, in August 1962. It wasn't allocated to a particular squadron and was classed as the Station reserve aircraft, coded C. This state of affairs remained until April 1963 when it was transferred to 210 Sqn. and coded Y. This was the only time that a Shackleton was held in reserve in this manner. As the sixties progressed and the Defence Budget increasingly came under pressure, Station Flights became an expensive luxury and started to disappear.

204 Goes Sea Skimming

A near catastrophic incident befell a 204 Sqn. crew on 19 April 1961. WR957/R had successfully completed a tiring15 hour Navex and was making a simulated attack on the local radar buoy moored off the coast. In the darkness the aircraft descended too low in the approach, and at the last minute the pilot started to climb, but not before the aircraft hit the sea and bounced back up again. The radar operator reported a loss of picture, which was subsequently found to be due to the scanner being torn out of the bottom of the aircraft. A safe landing was made at Ballykelly when it was discovered that in addition to the radar scanner the cameras and tailwheel doors were missing, and the fins, rudders and bomb doors had been dented. It was an incredibly lucky escape, and testament to the strong construction of the Shackleton.

Memorable Events at Home

The Aird Whyte Trophy, competed for by all Coastal Command squadrons, was from 1961, based around an actual sortie against a submarine operating in a prescribed area, plus a theoretical tactical exercise carried out at JASS. The first competition carried out under this format was won by 203 Sqn.

Another notable, if not amusing, event took place on 12 May 1960. The Air Officer Commanding 18 Group decided that the format of his annual inspection would be a test of operational efficiency instead of the customary parade. This was in the era of the four minute warning and the threat of nuclear holocaust, and the object of the exercise was to get as many of the based aircraft airborne in the shortest possible time, so that they could fly off to safe dispersed airfields. Inevitably word got out and most crews were in their aircraft, checks complete before the AOC had even arrived! When the signal to take off was received imagine the noise (and congestion) as the aircraft queued to get on to the runway. The locals must have thought it was the real thing!

A notable record was set in March 1963 when WR964/Q of 204 Sqn. stayed aloft for 24 hours 36 minutes, the longest recorded Shackleton flight.

New Residents

Due to the closure of RNAS Eglinton six miles up the road, a new unit moved into purpose built premises on the south side of the airfield at Ballykelly on 6 February 1963. This was No.819 Naval Air Squadron, equipped with three Wessex HAS 1's. This was the second time that the squadron had been based at Ballykelly, the previous time was for three weeks in April 1941 for anti-submarine training off HMS Archer. Aircraft on strength at the time of the move were:- XM872/320; XM931/321 and XM916/322, with a further two arriving in July:- XP145/323 and XM921/324. The squadron's task was anti-submarine training and perhaps also to keep a watch on the approaches to the Faslane submarine base, at which the first British nuclear attack submarines were starting to be based. It was well known that Soviet submarines regularly probed the area, and 'fishing trawlers' festooned with antennae were almost permanent fixtures anchored just outside territorial waters, observing the comings and goings during exercises and JASS courses.

The squadron also was regularly detached to aircraft carriers and helicopter support ships for short cruises. The helicopters were finished in standard Royal Navy anti-submarine scheme, with the red hand of Ulster in a white disc below the tail rotor. Later, a large squadron badge was added aft of the cockpit. At the time they were the only military helicopters based in N. Ireland, and as such were occasionally called out on SAR missions around the coast.

The Orion Makes its Debut

In May 1963 a major NATO exercise Fishplay VII was held. It had major implications for the squadrons at Ballykelly, 203 moving to Keflavik, Iceland, and half of 204 going to Aldergrove for the duration. These moves were to make way for an influx of visitors, Neptunes of the Aeronavale and VP-24, USN, and making its first visit to Ballykelly, the P-3A Orion. Four examples arrived from VP-8 at Patuxent River, Maryland, and were the centre of attraction of the remaining Shackleton crews at Ballykelly, as the Americans considered them to be state of the art as far as airborne submarine hunting was concerned. The noise levels were so different, purring turboprops as opposed to the growling Griffon piston engines of the Shackleton.

New Squadron Standards

Shortly after the completion of Fishplay, preparation got underway for a unique ceremony; the presentation of new Squadron Standards to all three squadrons on the same occasion by HRH Princess Margaret.

PART 5 - CONSTRUCTION AND CONFRONTATION (1964-1967)

Ballykelly had now been operational in its second period of activity for more than ten years and in order to ensure that the station continued to be able to carry out its many and varied duties, development had to take place.

Major Building

As 1963 started, a number of major building projects had been completed, including a new Sergeant's Mess. However, further improvements were planned that would enable Ballykelly to operate the next generation of maritime patrol aircraft to be adopted by the RAF.

One of the facts of life about the continual development of an aircraft type is that it will inevitably increase in weight, which in the absence of more powerful engines mean a requirement for longer runways. In 1943 the main runway had been extended to around 6000ft. to allow the later marks of Liberator to operate at maximum weight. This had necessitated crossing the main Londonderry-Belfast railway line and it was decided that trains had preference over aircraft! Now, the same runway was to be lengthened at the 09 end for a second time, to 8000ft. At the other end, V-Bomber scramble pads were constructed to enable the station to carry out its role as a dispersal airfield for four Vulcans.

The most obvious development, however, had to be the construction during 1964-65 of a large new hangar near the two existing hangars belonging to the former ASF(now more properly called the Engineering Wing), which was capable of housing six Shackletons at one go. Additional workshops, stores and hardstandings were also provided, with new roadways linking the engineering area with the main accommodation areas up near the main gate in Ballykelly village.

The engineering area was situated behind the squadron offices and dispersals, accessed over a bridge off the taxiway stretching between the thresholds of runways 27 and 03. Along this taxiway, from the 03 end were first, numerous dispersals built during the war and used for visiting aircraft. Over to the right in the corner was the 819 Sqn. Next was 204 Sqn. and hangar No.3, followed by ASWDU's offices and two dispersals. The taxiway then straightened, with 203's offices and dispersals to the left and the squadron's T2 hangar (No.2), to the right. Carry on over the 27 threshold, and you arrive at 210's area, hangar No.1 and newly constructed dispersals, the only accommodation north of the east-west runway.

Far East Detachment - Part 1

As 1964 progressed, Indonesia was increasingly infiltrating insurgents, first into Borneo and then into parts of Malaysia. In May 204 Sqn. sent out a detachment to Changi to undertake survey work in the area. The detachment, consisting of WR964/Q; WR966/O and WG555/N, left on 19 May. Route and flying times were as follows:-

- Ballykelly - El Adem: 12hrs 15 mins.

- El Adem - Khormaksar: 10hrs 15mins.

- Khormaksar - Gan: 9hrs 35mins.

- Gan - Changi: 9hrs 45mins.

- Total Flying Time: 41hrs 50 mins.

A number of survey flights were flown from Changi between 29 May and 10 June, the aircraft leaving for home on 14 June, arriving on 19 June. Flying time on return leg was 42hrs 45mins.

Far East Detachment - Part 2